Cre:https://en.sake-times.com/

Most fans of sake know that it comes in a seemingly endless array of permutations that vary, to degrees, in taste, aroma, and texture. But fewer are aware that you can further toy with a sake’s qualities simply by altering the vessel that it’s served in.

So let’s take an introductory look into the power of the sake cup, by examining the three main factors about these vessels that dictate how we perceive sake’s taste: shape, material, and thickness.

Shapes

The shape of the cup is probably the biggest determining factor affecting taste, because it dictates the sake’s exposure to air and funnels the drink’s aroma. The following diagram shows four common shapes of sake glass:

In the top left is a bud-shaped glass with a narrow rim the helps trap the fragrance inside the glass so it mingles with the flavors while drinking. This style is said to go well with aged sake.

Next to it, in the top right, is a straight-type cup that prevents the aroma from emerging, imparting only the unadulterated flavor of the sake itself. This may not actually be a good thing with, as that variety’s fragrance is one of the biggest factors in its overall appeal.

In the lower left is a bowl-type cup whose very wide rim exposes more of the sake’s surface area to air. This achieves a mellower taste that gently and gradually fills the mouth. It also highlights a drink’s nose and palate, which is why it’s also the preferred shape for wine glasses, too.

Finally, at the bottom right is the horn-type cup, which accentuates the bouquet of the sake. This might be the one you want to try in order to get the most out of the aforementioned daiginjo.

Material

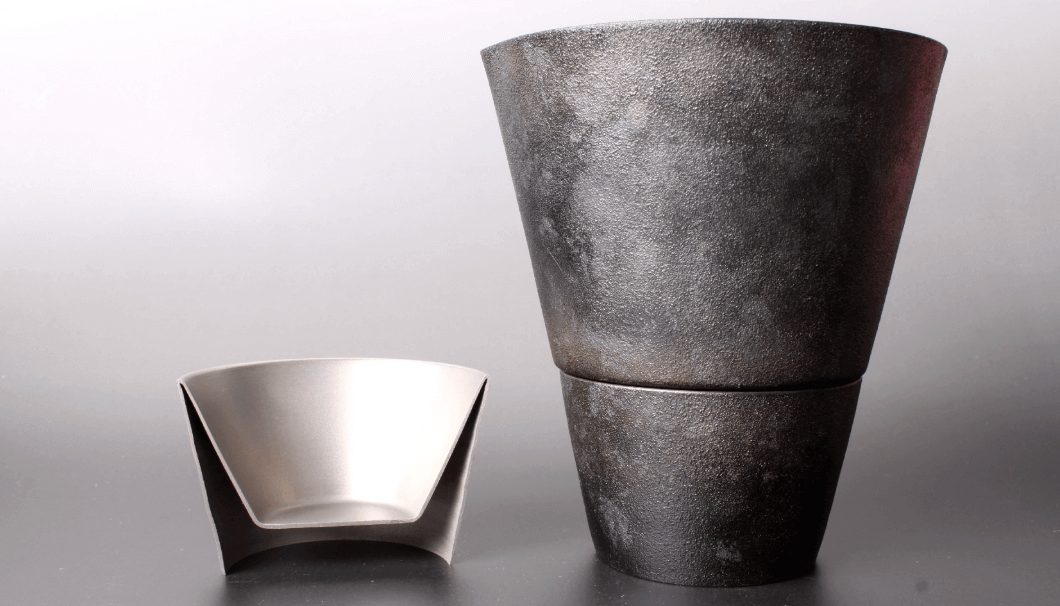

Sake cups come in more materials than you might expect. Of course, good old glass is always an option and will bring out a sake’s sharpness. On the other hand, woods like Japanese cedar or Japanese cypress have their own innate smells that tame a sake’s edge for a more mellow experience.

Porcelain and other ceramics also tend to soften the flavor of sake, but as varied as this material is, so is its potential effect on flavor. The smoothness of a fine china or the toughness of a traditional Japanese earthenware cup all bring something a little different to the table.

It’s even common to drink sake from cups made of metals like copper or tin. Some say the ions in the metals influence flavor, but there’s little hard evidence for that. More importantly, metal cups are great when enjoying a warm or chilled sake because they allow for more rapid temperature control.

Thickness

Even the thickness of your cup can affect the taste of what’s inside. Thicker glasses are said to soften the taste whereas thinner glasses give the sake more of a kick.

Some establishments might even offer you a choice in glass thickness. If you find yourself in this situation, a good strategy might be to begin with a thin glass. This is because your tongue is most sensitive during your first sips; a thin glass punches up the sake, letting you get the full flavor while your tongue is still primed to pick up on a drink’s complexities. Afterward, as your taste buds gradually become less receptive, you can switch to a thicker vessel.

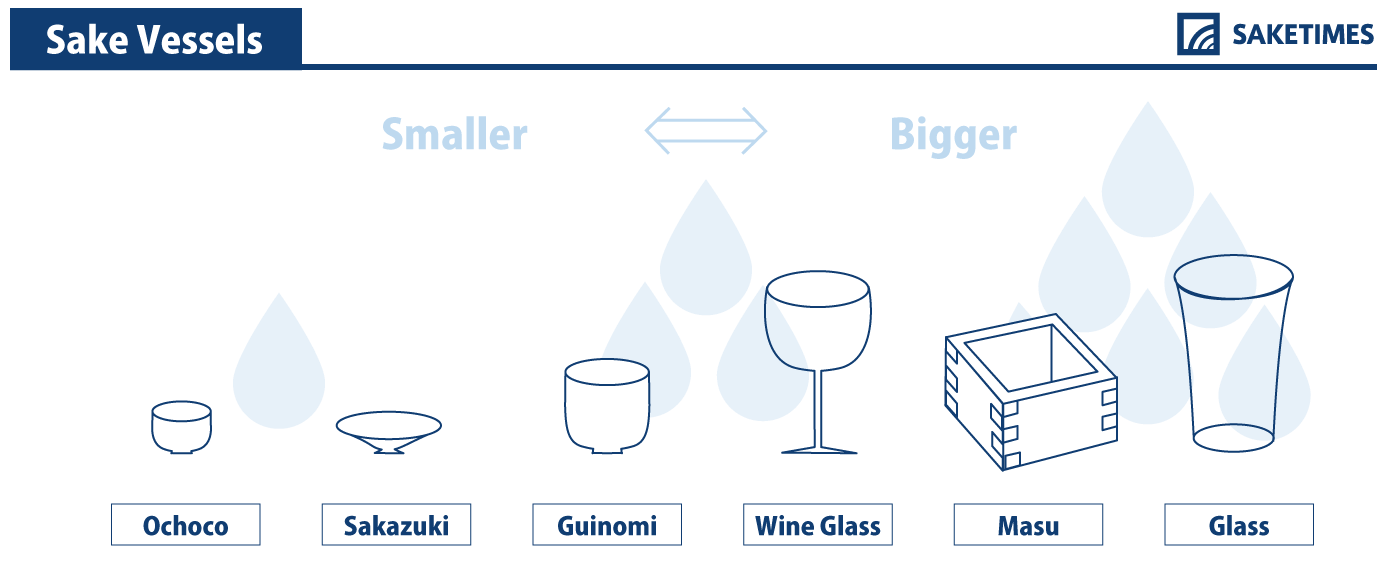

Now that you have a sense of the individual factors that define a cup’s effect on the taste of sake, let’s look at some standard styles of cup and put that knowledge to use in imagining how a serving of a robust junmai or a fruity daiginjo might come across when tasted from each.

Ochoko

These tiny cups can be made from any material and might be mistaken for shot glasses by the uninitiated. But, these are absolutely not for taking slugs of sake.

Their diminutive nature is by design, though, as it doesn’t leave much time for chilled sake to get warm and vice versa. Moreover, in Japan it’s customary for drinkers to fill and refill each other’s cups. So, small cups mean more filling and more social interaction.

Ochoko are probably the most symbolic cups for sake; the universal depiction of sake is an ochoko and tokkuri carafe, after all. No matter what phone or computer you’re using, calling up the “sake” emoji will almost certainly give you this iconic pair.

The prevalence of the ochoko and tokkuri set often leads to the mistaken impression that they’re the original sake vessels, but their introduction in the Edo period was actually relatively recent.

Guinomi

This is a slightly larger version of the ochoko intended for heavier drinking sessions. Some say that the name itself comes from an onomatopoeia for gulping. Sometimes, beginners might have trouble distinguishing a guinomi from an ochoko, but the main differences are simply size and a slightly wider rim on the guinomi.

Sakazuki

You don’t see many people hanging out at bars drinking from shallow and wide sakazuki these days, but its history as a sake cup is long and storied. Way back when it was more fashionable, people used to begin drinking sessions with a sakazuki and then move on to different cups. You might find this custom continuing in certain formal situations such as traditional Japanese weddings, where the bride and groom take sips of sake from three different sakazuki.

Masu

Although almost as iconic as the ochoko, these wooden boxes aren’t often regarded as cups themselves. Some restaurants may even serve a glass sitting inside a masu with the sake spilling over the rim of the glass and into the box, to the confusion of some.

Rest assured it is okay to drink straight from the masu and doing so was the norm during the Edo period. It’s easiest to imbibe from the corner of the masu, and many would traditionally sprinkle salt here before drinking.

Wine Glass

In recent years, wine glasses have become popular for consuming sake. Renowned wineglass maker Riedel have even developed their own line of premium cup.

Riedel’s junmai-specific glass

Non-Japanese people might be hesitant to use wine glasses, worried that it’s a slight to sake culture and heritage, but most breweries and experts have embraced it, showing that despite being steeped in tradition, sake brewers and enthusiasts can be very forward-thinking.

Ika Tokkuri

If you’ve already mastered the above cups, then you might want to take an advanced course with the ika tokkuri. “Ika” is the Japanese word for squid and, as the name suggests, this is a carafe made of the hollowed outer body of the eponymous cephalopod.

As a general rule, sake cups don’t actually alter the chemical composition of the sake…unless the cup is made of squid, in which case you can expect your drink to change color and take on a mild briny quality.

We probably wouldn’t recommend giving your finest sake the ika tokkuri treatment, but it can be a fun experiment with something a little more budget-conscious.

Which is the Best Cup?

So, which style, shape, material, and thickness of cup is ideal for sake in general? Well, there is no answer to that question. As experts like Miyashita will readily tell you, preparing sake is an art, not a science, and there is no definitively perfect cup.

The “best cup” might depend on an endless list of variables like the food you’re pairing a sake with, the decor of your dining room, or even the mood you happen to be in at that moment. But above all, it’s a matter of personal preference that only you can discover for yourself.

It does take some practice, but since this kind of training really only involves drinking sake and shopping, you’ll find it’s definitely one of the more fun skills to build out there.